Man in the Middle

Published as "Man on a Mission" in DS News Magazine, June 2012

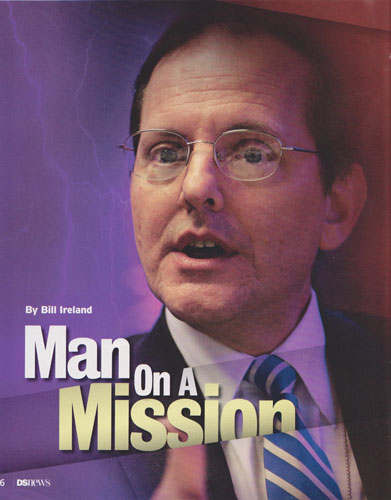

He's been called "the most powerful man in housing policy," but labels like that don't seem to mean much to Edward DeMarco. His current role as Acting Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) is just the latest stop in a long government career that has equipped him uniquely to address the troubles of today's mortgage market. He approaches it with calm determination, drawing on his prior experience at the Treasury Department, the Social Security Administration, and the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO). In a rare exclusive interview, DeMarco reflected on the responsibilities of overseeing the nation's mortgage giants, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

"Well, it's certainly been challenging," he says, using a word that crops up often in his conversations. He then quickly deflects the focus from himself to the broader picture: "But you know, I think that everyone involved with housing finance issues, whether they're policy makers or frankly, homeowners, they've found the environment of the last four to six years very—challenging."

Edward DeMarco chooses his words carefully. His critics are often less restrained. Katrina vanden Heuvel, writing in The Nation, declared, "Edward DeMarco has slowed the economic recovery with the stroke of a pen. His actions are costing taxpayers tens of billions of dollars, forcing millions of homeowners to lose their homes, and contributing to the falling housing prices that are a brake on the recovery."

Figures as diverse as Sen. John McCain and California Attorney General Kamala Harris have called for his head. Earlier this year New York Rep. Jerrold Nadler led a group of legislators and activists that arrived on Capitol Hill with a petition demanding his removal. "He is standing in the way," Nadler later told the Huffington Post. "If he doesn't do what he ought to do, then he ought to be fired."

That's not so easy, as it turns out. The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 which established the FHFA allows the President to replace the Director "for cause"—but not simply for implementing unpopular policies. When his predecessor James Lockhart resigned in 2009, DeMarco, then Chief Operating Officer, was designated Acting Director. Obama tried to replace him in 2010 with North Carolina Banking Commissioner Joseph Smith, Jr., but the nomination stalled in the Senate. And with the controversy over Richard Cordray's appointment to head the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, another recess appointment was politically impractical. So, to the chagrin of his opponents, Edward Demarco remains firmly in place.

The Lightning Rod

How did a self-effacing economist become such a lightning rod for controversy? It all revolves around the newest perceived fix for the mortgage crisis: principal forgiveness.

12 million homeowners are underwater on their loans. If they could just eliminate that negative equity, the reasoning goes, they'd lead a housing recovery that would spur the economy overall. And by refusing to allow the Enterprises under his control to write down principal amounts, Edward DeMarco has prevented that from happening.

All along, DeMarco's position has been simple. As he explained in a C-SPAN interview last fall, "Principal forgiveness does not accomplish our conservator mandate." While that response left critics gasping in exasperation, he basically stuck to it in subsequent statements.

In January, 2012, the Treasury Department raised the stakes by tripling its incentive payments to mortgage investors that use principal write-downs in loan modifications. The same month, the FHFA released the analyses that had led the agency to reject principal forgiveness as a loss mitigation option. Citing the "statutory mandate to conserve the assets and property of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac", the release also highlighted the agency's central dilemma in formulating policy: how to balance the needs of distressed homeowners with the rights of taxpayers who were footing the bill. In an intriguing coda, it noted that "changing circumstances may call for an updating of our analysis."

A Growing Wave

Meanwhile, the demand for principal write-downs was growing. It may have begun with disgruntled homeowners and policy wonks, but was soon picked up by public figures harder to ignore: Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shaun Donovan both voiced support for the idea. They also happen to sit on the Federal Housing Finance Oversight Board, which advises the FHFA. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who is also heading a presidential task force investigating Fannie and Freddie, has strongly supported principal forgiveness; so has New York Federal Reserve Bank President William Dudley, and even DeMarco's predecessor James Lockhart.

In January of this year the Federal Reserve issued a white paper that endorsed principal forgiveness as one of several recovery tools. And in April the International Monetary Fund (IMF) joined the fray with a white paper of its own, urging adoption of a debt forgiveness program modeled on the Home Owners' Loan Corporation that President Franklin Roosevelt established in 1933. With such a formidable cast of proponents, the idea gathered momentum through 2011 and beyond.

On May 1, Reps. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) and John Tierney (D-Ma.) released a letter accusing DeMarco's agency of making decisions based on "ideology" rather than "data and analyses", possibly causing "unnecessary losses to U.S. taxpayers." They cited documents received from an anonymous former Fannie Mae employee, purportedly showing that internal analyses at the agency actually favored principal forgiveness. But the programs were allegedly quashed by other Fannie officials who harbored a "philosophical" aversion to the policy. The letter further implied that DeMarco had deliberately withheld these documents.

A Matter of Trust

To at least one former colleague who has known DeMarco for over 20 years, those charges don't ring true. Armando Falcon is Chairman and CEO of Falcon Capital Advisors, and a former Director of the OFHEO, where DeMarco later served as Chief Operating Officer. "I've always known Ed to be a straight shooter who tries to be as objective as possible in doing his job," Falcon said in an interview. "I've never known Ed to be an ideologue. So I don't think descriptions of him in that way are accurate." As DeMarco himself pointed out in his response to Reps. Cummings and Tierney, the FHFA had initiated several pilot programs involving principal forgiveness as far back as 2009, which would tend to deflate the charges of ideological bias.

Falcon himself knows something about being at the center of controversy: As head of OFHEO he pursued an investigation of Fannie Mae that led to the ouster of then-CEO Franklin Raines in 2004. Like DeMarco, he aroused the ire of powerful political players, and had to persevere against strong headwinds. "You've got to stay focused on just doing your job, and not get distracted because of external pressures," Falcon observed. "It'd be so easy to give in to political pressure and just do what a lot of powerful forces would like you to do. But then you're not fulfilling the oath of office that you took."

Facing his own pressure and criticism, DeMarco remains philosophical. "No one likes being put in that position," he says, "but I understand the frustration. It doesn't deter me from making sure that FHFA carries out its responsibility in a thoughtful way. There are big challenges facing the country's housing system. There are a lot of borrowers in distress, and there are a lot of taxpayer dollars that have already been spent through this housing and financial crisis. And we are working diligently to simultaneously provide relief to troubled homeowners, stability to the housing market, and protection to taxpayers. In that mix, trying to satisfy those three objectives, you're never going to make everyone happy. But we're trying to be consistent and we're trying to be transparent in how we're going about carrying out those responsibilities."

That stubborn attention to the public trust—regardless of politics—resonates throughout DeMarco's public and private declarations. It's no surprise to Michael Ortman, who has known him since they were both students at the University of Notre Dame 30 years ago. "He just wants to serve the public," Ortman said in an interview. "He didn't ask for the role he's in; he does it sincerely and honestly and honorably." Their friendship worked out well for Ortman: Ed introduced him to his sister, whom Ortman later married. Not surprisingly, they're both fiercely supportive of him. "I could tell you," he says, "The whole family is so proud of what he is doing and what he has done."

The Numbers

DeMarco revisited the principal forgiveness issue in an April 4, 2012 speech at the Brookings Institution, showing with graphs and statistics the outcomes from various loss mitigation approaches.

The figures showed that borrower performance on HAMP modifications was only loosely related to variations in loan-to-value, hovering between 72 and 76 percent regardless of how underwater the borrowers were. For non-HAMP proprietary modifications, the range was 70-74 percent. This undercuts a primary argument for principal write-downs: that if borrowers remain severely underwater after a modification, they'll be more likely to re-default. But these borrowers had already demonstrated a willingness to accept modifications with no reduction in principal, so any re-defaults would likely reflect inability to pay, not unwillingness. Negative equity does increase the likelihood that homeowners will default in the first place, as DeMarco acknowledged.

On the other hand, statistics showed that borrower performance on modified loans was closely tied to reductions in monthly payment amounts. The message: Borrowers who agree to modifications will generally keep paying if they can. So the key to success is to find ways to cut the payments to affordable levels. DeMarco argued that the tools already in place were sufficient to accomplish that: interest rate reductions, loan term extensions, and principal forbearance. These methods could achieve the goal without the irreversible investor losses that principal write-downs would incur.

He also touched on a point that is commonly misunderstood: Any principal reduction would only be applied as one of several loss mitigation tools, and only on a portion of that minority of loans that is delinquent. As he put it:

The larger worry in implementing a principal forgiveness program is how it would impact the majority of borrowers who remain current, even though they may be underwater. How many of them would intentionally default to gain the same benefits as their delinquent neighbors? A stampede of "strategic modifiers" could inflict unacceptable losses. On the other side of the ledger, borrowers without any hope of regaining equity would also be more inclined to default. Any FHFA policy must navigate between those two perils.

In his Brookings speech, DeMarco outlined the conditions under which principal forgiveness might work. "... It would have to be clear and transparent," he said, "having a basis in the conservatorship mandate and a general acceptance of reasonableness if not fairness."

The Bottom Line

Eventually, the impossible expectations placed on this one loss mitigation tool will wane. And Edward DeMarco will continue his tedious task of unwinding the mortgage mess, one step at a time. But, grasping for a more poetic description of his task can lead to some unexpected humor:

"What inspires you to get up every morning and go to work?"

"My alarm clock."

When the laughter subsides, Ed DeMarco reverts to form: "Honestly, I think it's what I said before; I've been a career public servant; I care deeply about this country, I care deeply about taxpayers, and the opportunities for homeownership, and we've got a very important mission at FHFA, and I'm dedicated to doing the best I can and the best that the agency can in carrying out that mission. That's what inspires us. There certainly are problems out there that need thoughtful and vigorous attention and response, and we're trying to deliver that."

As his brother-in-law Michael Ortman observes, "What you see on C-SPAN and elsewhere is what you get. That's Ed. There's not a hidden agenda. There's not an aspiring politician, there's none of that. He's just a very humble and very principled public servant. And that is so rare in our culture today that no one seems to know how to deal with it."

# # #